The Hunt for the “100-Bagger": From Theory to a Working Screener

Recently, I read the excellent book 100-Baggers by Christopher Mayer. The book is a fascinating study of 365 stocks that each turned $10,000 into a million.

But… there’s a world of difference between reading about success and actually finding tomorrow’s “multibaggers”.

So I was eager to see whether the insights from the book could be translated into something concrete: a working “Trading Idea” inside ChartMill.

The 5 Pillars of the “100-Bagger” Machine

To cut through the market noise, I built this screener around the five quantitative fundamentals Mayer identified, adjusted for today’s market.

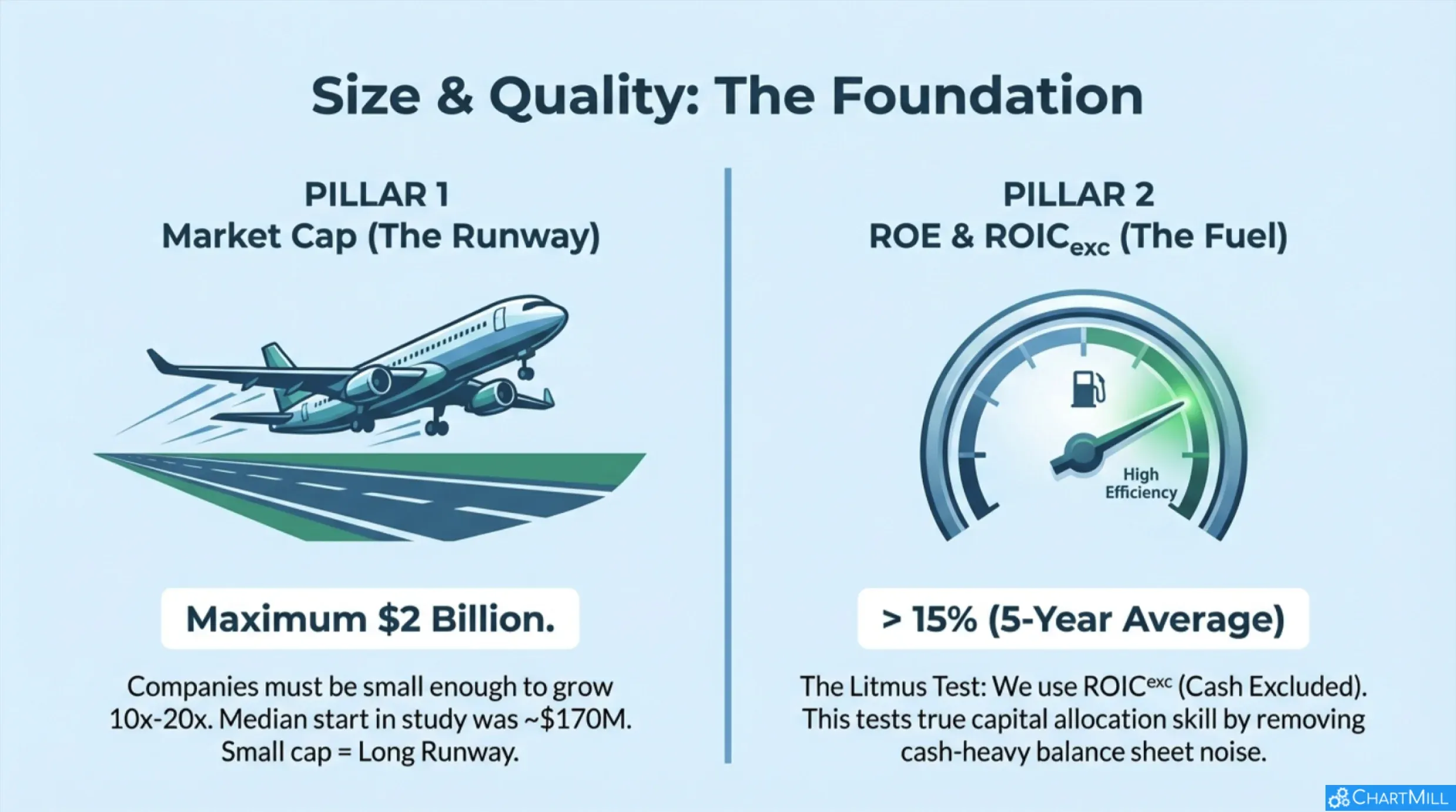

1. Starting as an “Acorn” (Market Cap > $2 billion)

In the book, the median sales figure for successful 100-baggers at the start of their run was approximately $170 million. Focus on companies that are substantial enough to have a proven business model but small enough to leave a massive "runway" for expansion.

Mayer wrote the book in 2015 and used an upper limit of $1 billion. Partly due to inflation, you can raise that threshold to $2 billion to find more candidates, but remember: the smaller, the better!

In this screener, we use a maximum market cap of $2 billion.

2. The Engine: ROE & ROICexc of 15%+ (5-year average)

This is the heart of the strategy. The single most critical ingredient in a 100-bagger is the ability to earn high returns on capital and, crucially, the ability to reinvest those profits at similarly high rates.

We’re not looking for a lucky break, but for businesses that have proven they can reinvest capital extremely profitably year after year.

The Check & Balance: ROE vs. ROIC

Why look at both?

A high ROE (Return on Equity) is great, but it can be misleading if a company takes on a lot of debt, since that debt isn’t included when calculating return on equity.

ROICexc (Return on Invested Capital, cash excluded) is the litmus test: it looks at returns on all capital, including debt.

A company that averages above 15% on both metrics over five years is exactly what we’re looking for.

Opinions are divided as to whether or not excess cash should be included in invested capital. According to some, this cash should indeed be included. After all, cash that is on the balance sheet is a deliberate choice by management, and so an appropriate return should be made on it.

The second group, however, believes that excess cash does need to be filtered out because the ROIC calculation and capital allocation should be kept separate. If you choose to do otherwise then you actually hold the company responsible for capital that is not used to generate operating income.

However, this defeats the purpose of a ROIC calculation. It is precisely by removing that excess cash that a more accurate picture of shareholder value creation emerges.

More info in this article

3. Growth Momentum: Revenue Growth > 10% (5-year average)

You cannot achieve 100-bagger status without "growth, growth, and more growth"...

Without ongoing expansion, you’ll never reach 100-bagger status. The screener looks for organic revenue growth of at least 10% per year (5-year average).

4. Skin in the Game (at least 10%)

We’re looking for entrepreneurs, not managers.

That’s why we filter for companies where insiders own at least 10% of the shares. In a $1 billion company, that’s still $100 million, enough to ensure the CEO views the business through the same lens you do.

5. Gross Margins: The “Moat” (Gross Margin > 30%)

High margins are proof of a competitive advantage. Companies that must compete on price (low margins) rarely have the breathing room to become 100-baggers.

Screen for companies with high gross profit margins (+30%) relative to their industry peers.

6. No or Low Dividend (< 1%)

For a 100-bagger, a dividend is a “leak” in the growth engine. We want the company to reinvest every earned dollar internally at that high ROIC of at least 15%.

7. 100 Bagger Checklist

The Quantitative Gate vs. the Qualitative Treasure

A stock screener like ChartMill is an amazing filter, but it’s still a machine. It can scan millions of data points in search of that one high ROIC, but it can’t feel whether customers love a brand or whether a CEO is obsessed with a brilliant long-term vision.

Numbers as Indirect Evidence

Of course, the numbers do tell us something about quality. A ROIC consistently above 15% isn’t random, it’s indirect evidence of pricing power.

It tells us the business has a product or service customers are willing to pay for, even as prices rise. The machine can’t see pricing power, but it can see the profitability that results from it.

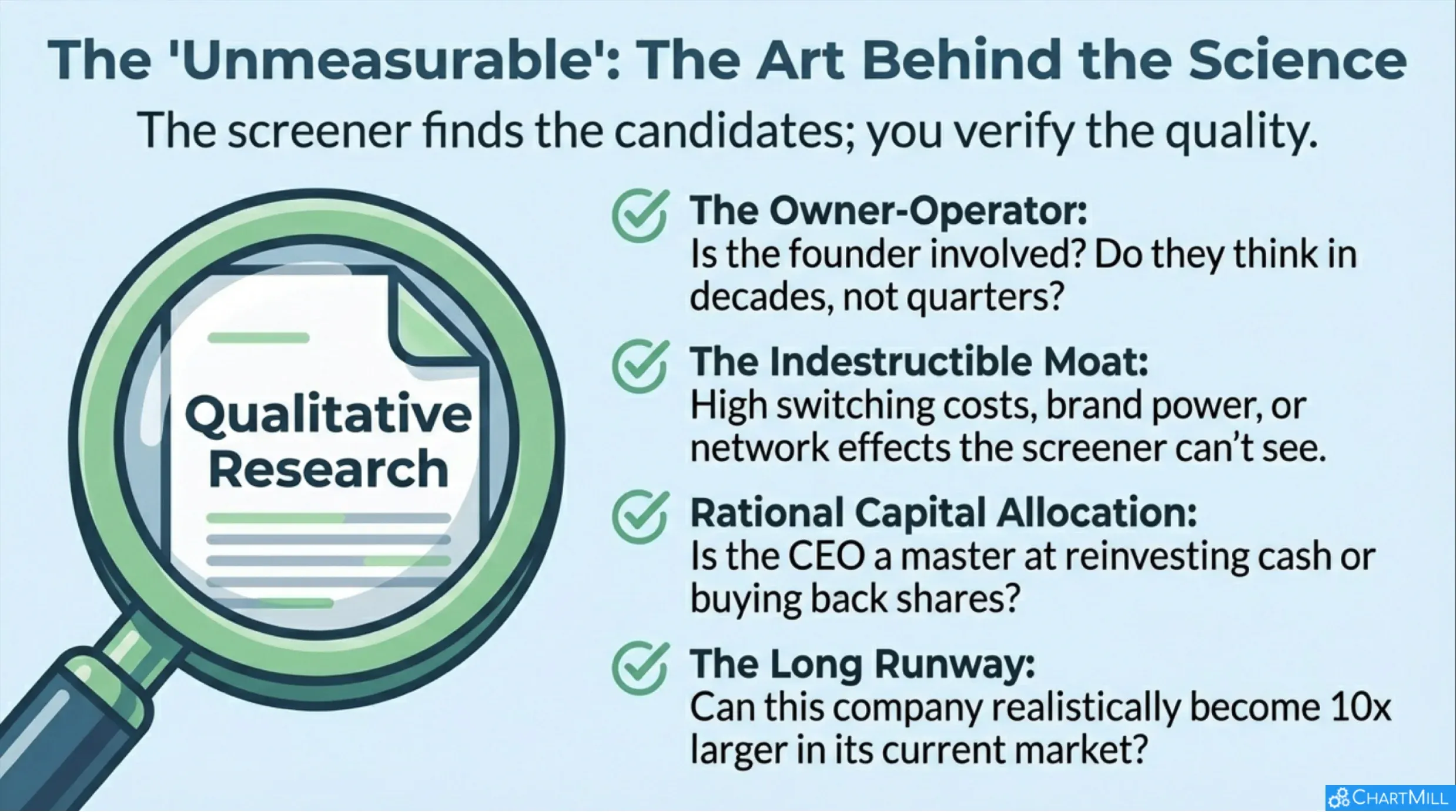

The “Unmeasurable” (The treasure behind the numbers)

The screener gets you to the front door, but the numbers are only the outcome of something deeper: business quality.

Once you have a shortlist, the real research begins into the “Alchemists” from Mayer’s book:

- The Owner-Operator: Is the founder still involved? Founders think in decades, not quarters.

- The Indestructible Moat: Why can’t competitors copy this? Look for high switching costs, strong brands, or network effects.

- Rational Capital Allocation: Is the CEO a master at reinvesting cash wisely, making acquisitions, or buying back shares at the right time?

- The “Long Runway”: Can this company become 10 or 20 times larger within its current market?

- …

Going deeper would take us too far off track in this article, so I’ll gladly refer you to the book where all of these facets are covered in detail.

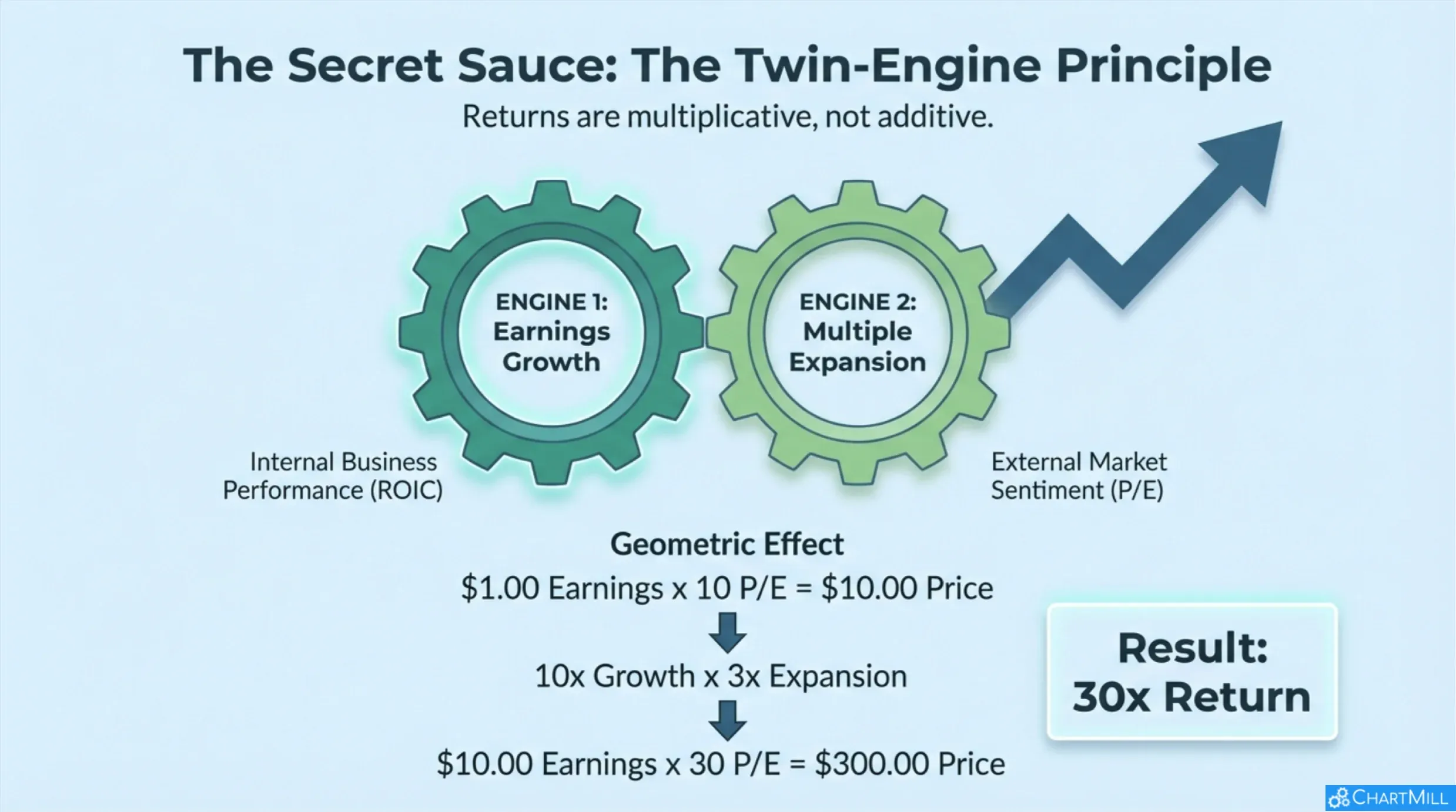

The Twin-Engine Principle: How 100-Baggers Take Flight

In Christopher Mayer’s study, the most explosive returns don't just come from a company doing well; they come from two distinct "engines" firing at the same time. This is a multiplicative effect, not an additive one.

Engine 1: Earnings Growth (The Internal Engine)

This is driven by the company’s actual business performance. Through high ROIC and smart reinvestment, the company grows its bottom line. Example: A company earns $1.00 per share today. After ten years of compounding and expansion, it earns $10.00 per share. That is a 10x increase in earnings.

Engine 2: Multiple Expansion (The External Engine)

This is driven by market sentiment, how much investors are willing to pay for those earnings (the P/E Ratio). Example: When you first bought the stock, it was an "ugly duckling" or undiscovered micro-cap trading at a P/E of 10. Ten years later, it’s a market darling, and investors are happy to pay a P/E of 30. That is a 3x increase in the valuation multiple.

The Magic: The Geometric Effect

The reason this is called the "Twin-Engine" principle is that these two factors multiply each other.

Using our example:

- Initial Price: $1.00 (Earnings) × 10 (Multiple) = $10.00

- Final Price: $10.00 (Earnings) × 30 (Multiple) = $300.00

Even though earnings "only" grew 10x, your total return is 30x. This "double whammy" is the secret sauce of every 100-bagger.

Why this matters:

Engine 1 is fueled by the ROIC and Sales Growth filters. You are looking for the fundamental power to grow earnings.

Engine 2 is made possible by the Small Market Cap and Lower Valuation filters. It is very hard for a stock that already has a P/E of 100 to benefit from Engine 2; in fact, its multiple is more likely to shrink (Multiple Contraction).

Summary:

You want to buy a great business when it’s still "relative cheap" and "small."

As the company grows (Engine 1), the world eventually notices and starts paying a premium for it (Engine 2). When both engines roar, that’s when you find your 100-bagger.

Reality Check: What if the Pool is Empty?

While testing this screener against a global database of more than 10.000 stocks, I hit a harsh reality: if you apply every single criterion with extreme strictness, you might end up with zero results. High quality is rare, and the market isn't blind to it.

The PEG Ratio Paradox

I have chosen to omit the PEG-filter (valuation relative to growth) entirely.

Even when setting a generous PEG cap of 2.0, I often found only a few candidates. A company boasting a 15% ROIC and consistent double-digit growth is rarely "cheap."

In a 100-Bagger strategy, initial quality is far more important than a bargain-bin price.

If your results list remains too short, use this Hierarchy of Flexibility:

- Expand the Market Cap ($2B – $3B): In today’s high-liquidity market, a $2.5 billion company is still very much a "small-cap" with plenty of runway to grow 10x or 20x.

- Relax the Insider Ownership check: Data on insider holdings can often be "noisy" or outdated in automated databases. It is better to verify this manually in the company’s latest proxy statement or annual report for your final candidates.

- Dividend Yield: Allow for a modest dividend (< 2%), provided the payout ratio remains low. Some elite compounders pay a small dividend simply to attract a broader base of institutional investors.

What are the absolute dealbreakers?

The quality metrics. ROICexc (> 15-20%) and Revenue Growth (> 10%) are the Holy Grail. If you lower these standards, you are no longer hunting for "elephants", you are buying mediocrity.

The Coffee Can Approach: Patience as the Ultimate Strategy

Finding a 100-bagger is not a game of speed, but a test of vision and conviction. By using this ChartMill screener, you have already moved past the noise and identified a rare group of companies with the financial "DNA" of a winner.

Here’s the direct link to the Multibagger Trading Idea in ChartMill (all filters ‘on’).

As pointed out in the article, the numbers are just the starting point. The real work begins with your own qualitative research into the management and the "moat," and the real reward comes to those who can practice the "lethargy" Mayer so highly prizes.

As the saying goes, the big money is not in the buying and the selling, but in the waiting. Load your "Coffee Can," stay disciplined through the inevitable volatility, and give your "acorns" the time they need to become giants.

Kristoff | ChartMill